15 May 2025

7 min read

Fungarium collection digitised! What interesting specimens have we uncovered?

As part of the Digitisation Project, our team has been working toward making our entire dried fungi collection available for global access.

We’ve hit an exciting new milestone on our multimillion-pound Digitisation Project having imaged our entire Fungarium collection, helping make it accessible to everyone around the world, for free via our new Data Portal!

Our fungi collection - one of the largest and most diverse on the planet - boasts over 1.1 million specimens. From the rarest mushrooms collected within remote jungles to fungi-parasitised tarantulas and historically fascinating specimens collected during legendary voyages – our Fungarium showcases some of the most unusual organisms on Earth.

It’s taken over 175 years to amass this unique collection, and it has become a vital source of knowledge supporting scientific and conservation work, while also supporting visiting researchers from the sciences, arts and humanities.

A milestone moment for fungal science

Our fungal collections are particularly rich in type specimens, with around 45,000 types. These are the original specimens that are used to make clear links between the fungus as a living organism and the name applied to it.

For the first time ever, these wonders are becoming just a click away for researchers, fungi enthusiasts, and curious minds around the globe.

Our Fungarium Collection Manager, Lee Davies commented:

“Seeing our massive Fungarium collection made available online is genuinely exciting. It means these specimens - some centuries old – from all over the world, are now accessible to researchers across the globe at the click of a button.

“I’ve spent years caring for this collection and promoting its use by all kinds of researchers - arts, humanities as well as scientific - it’s incredibly meaningful to know we’re sharing our little microcosm of the world’s fungal diversity in a way that supports science and conservation far beyond our walls."

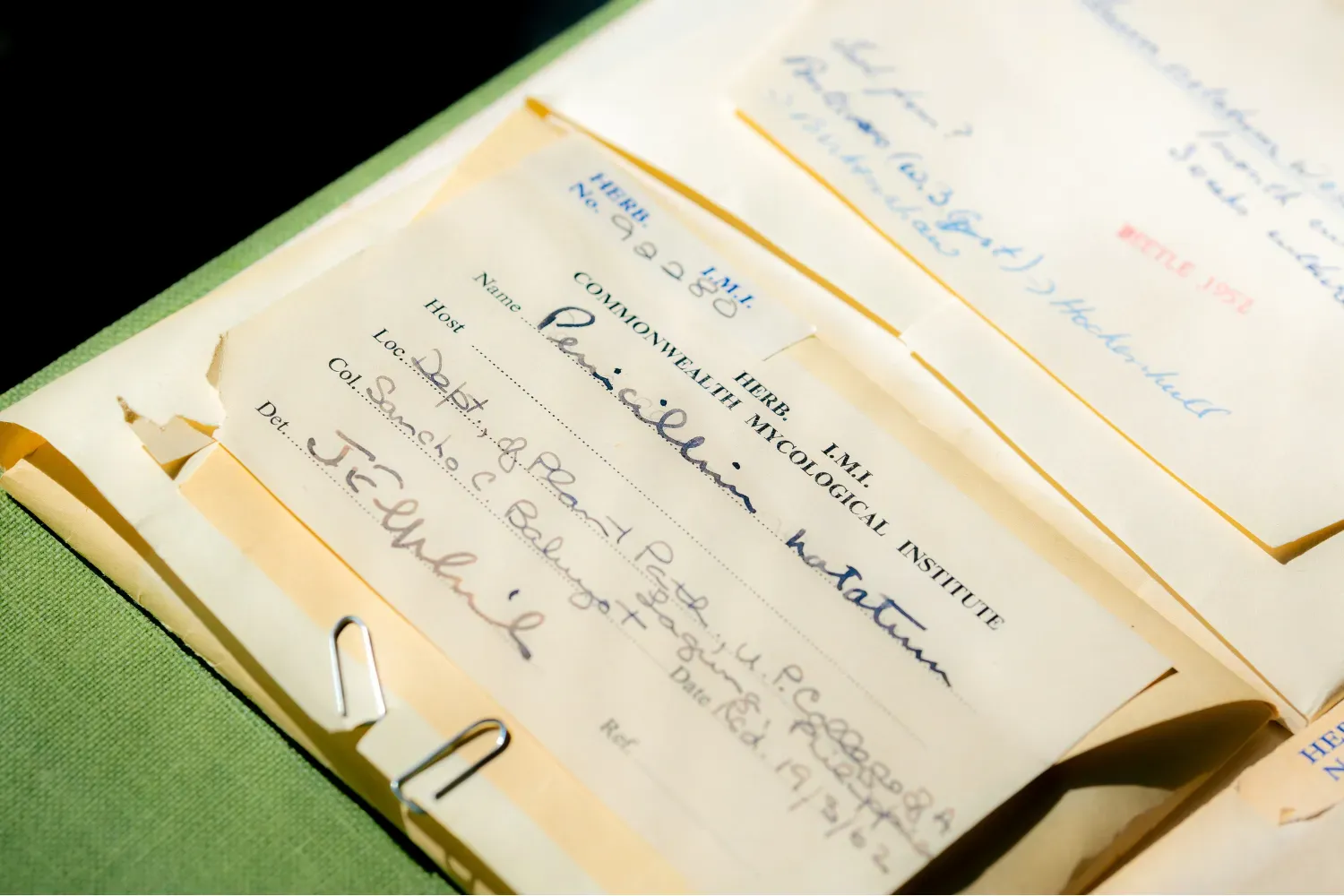

More than just photographs

Digitising our collection involves more than just taking photographs - it is about capturing the invaluable notes kept with the specimens, preserving historical data, and making all this information available online.

Our digitisation process is still ongoing with transcription and quality assurances - meaning there’s around 230,000 records out of the of the 1.1m specimens currently available on our Data Portal with more being added each week. However, here we are excited to share some of the most fascinating specimens that we have uncovered over the years:

1. David Attenborough’s ‘zombie fungus’ - Gibellula attenboroughii

Collected from the ceiling of an abandoned gunpowder store in Northern Ireland, Gibellula attenboroughii is a newly described species of spider-infecting fungus – and the first of its kind officially recorded in the British Isles. Discovered after appearing on BBC Winterwatch in 2021, it was found growing on an orb-weaving cave spider (Metellina merianae) and later confirmed as a new species through detailed morphological and genetic analysis.

Named in honour of Sir David Attenborough, this species belongs to a group of so-called ‘zombie fungi’, which hijack their host’s behaviour before killing them – in this case, prompting the infected spider to move to a more exposed position to better spread fungal spores.

2. Fungus collected by Charles Darwin – Cyttaria darwinii

Collected by Charles Darwin himself, Cyttaria darwinii is a truly historic specimen. Found during the HMS Beagle voyage in Tierra del Fuego (1831-1836), this bright orange, globular fungus parasitises southern beech trees. Described by Darwin as ranging in size 'from a bullet to a small apple' and having the 'colour of a yolk of an egg' this small globular fungus is parasitic and grows exclusively on southern beech trees (Nothofagus).

Samples of the fungus were brought back to England, where one of Britain’s first mycologists, Rev. Miles Joseph Berkely, gave the species its official scientific description and named it in honour of Darwin. Our digitised specimen offers a rare chance to see fungi through the eyes of one of history’s most iconic naturalists and links our collections directly to the foundational moments of modern biology.

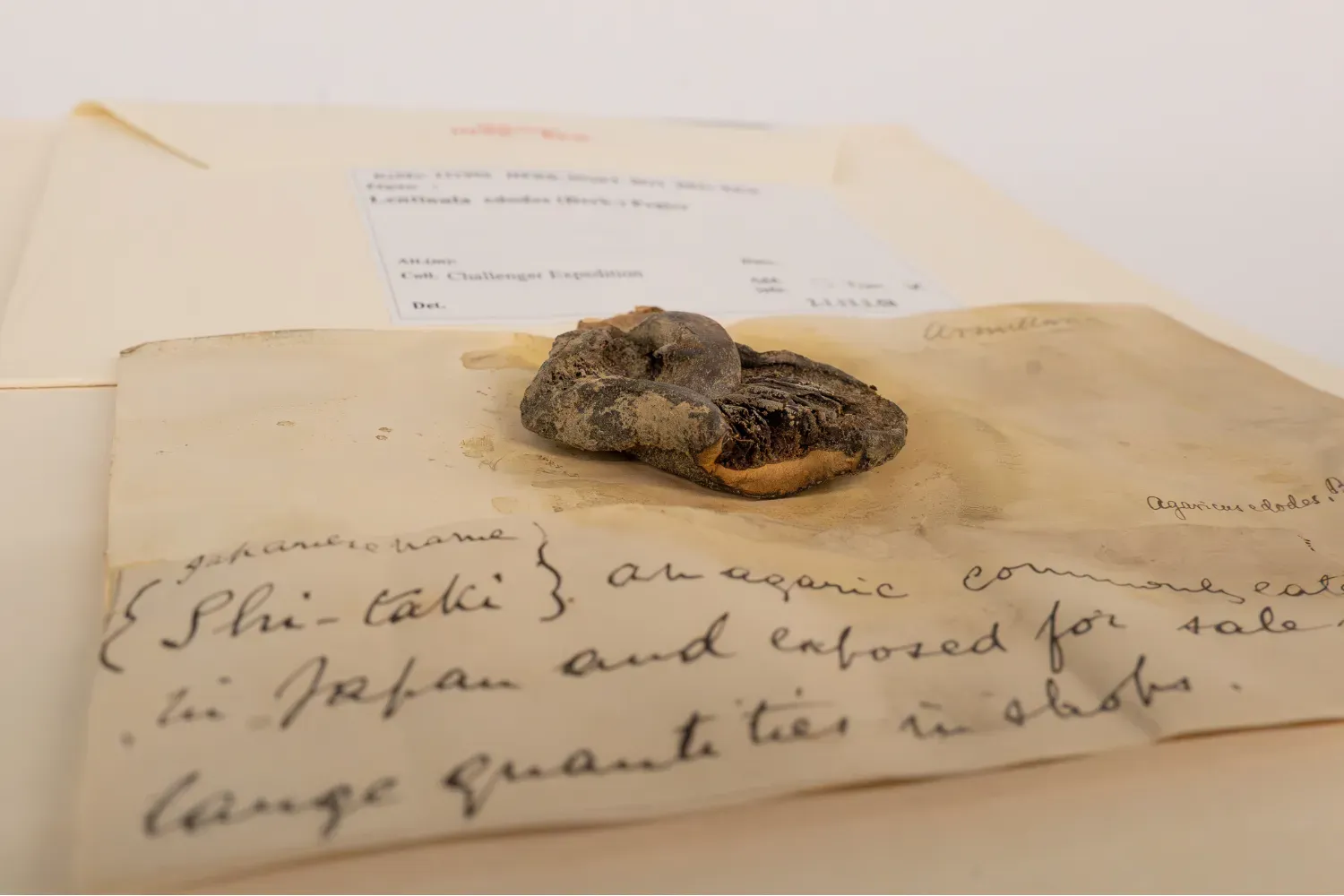

3. Shiitake (collected during Challenger Expedition) - Lentinula edodes

One of the world’s most widely cultivated edible mushrooms, Lentinula edodes - or shiitake - has a lesser-known British connection. This holotype specimen was collected during the Challenger Expedition (1872–1876), a pioneering global scientific voyage.

Described by Berkeley, this historical shiitake sample now also forms part of Kew’s Fungarium Sequencing Project, helping to unlock the genetic secrets of fungi past and present. It’s a perfect blend of culinary, scientific, and historical significance.

4. A whole latte trouble (coffee’s greatest enemy) - Hemileia vastatrix

Hemileia vastatrix - better known as coffee rust - is one of the most devastating plant pathogens in history. First observed in 1861, it spread across all major coffee-growing regions, reshaping the global beverage trade and leading to the rise of Ceylon tea.

This specimen collected in 1869 shows a critical moment in agricultural history and holds potential to support ongoing efforts to manage plant diseases in an era of climate change and global trade.

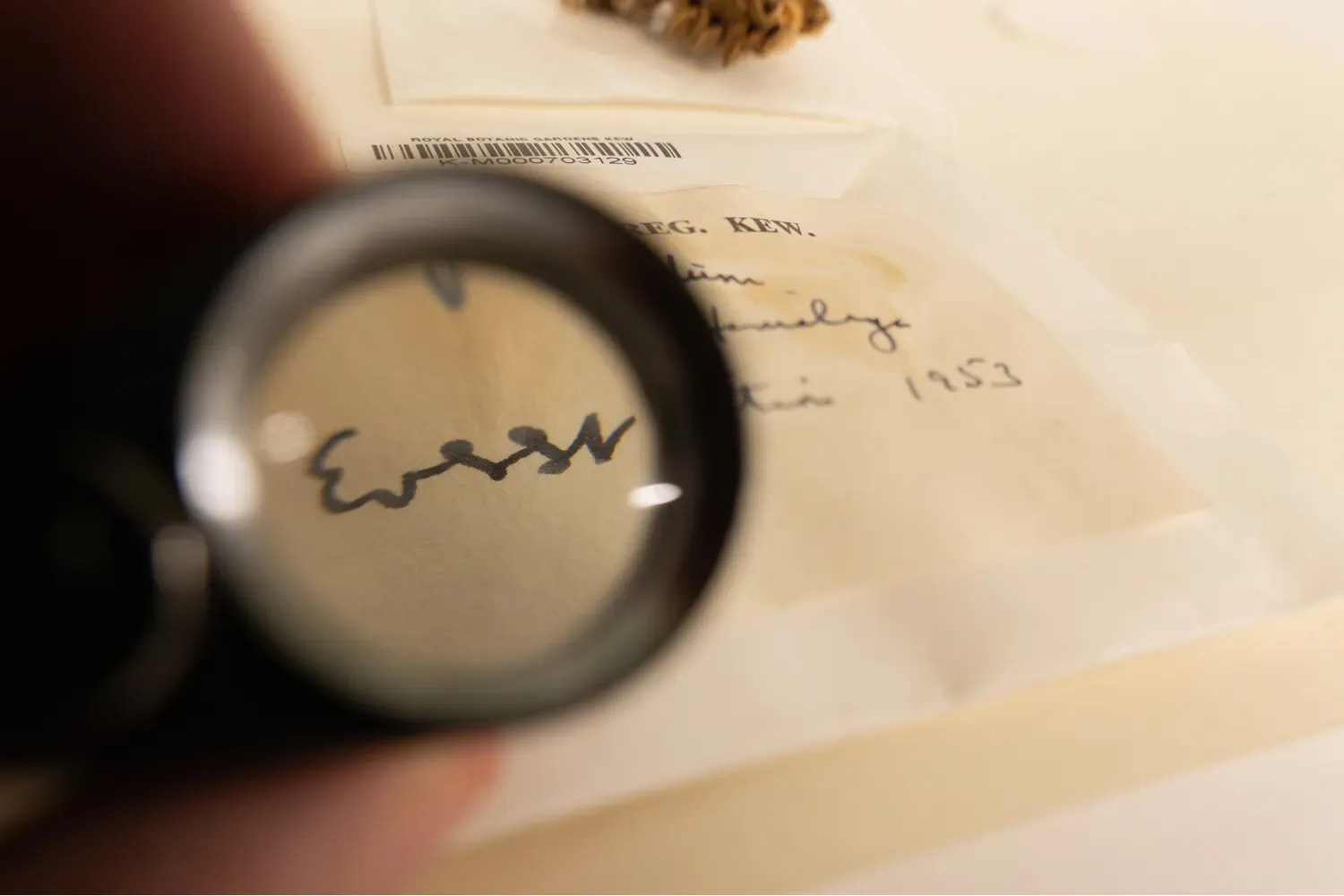

5. Fungus collected during first successful Everest Expedition

The only words written on this specimen are: “Stereum hirsutum, c. 15,000 ft, Nepal Himalaya, Everest Expedition 1953.” With no collector recorded, the details remain hazy – adding to the mystery.

There was only one major Everest expedition in 1953, and it was the one: the first successful summit of the world’s highest peak by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

It’s possible this specimen was collected during that historic climb - or perhaps during one of the earlier reconnaissance missions made that same year. Either way, it represents a rare glimpse of fungal life in extreme, high-altitude conditions – and the overlooked role of fungi in some of the planet’s most remote ecosystems.

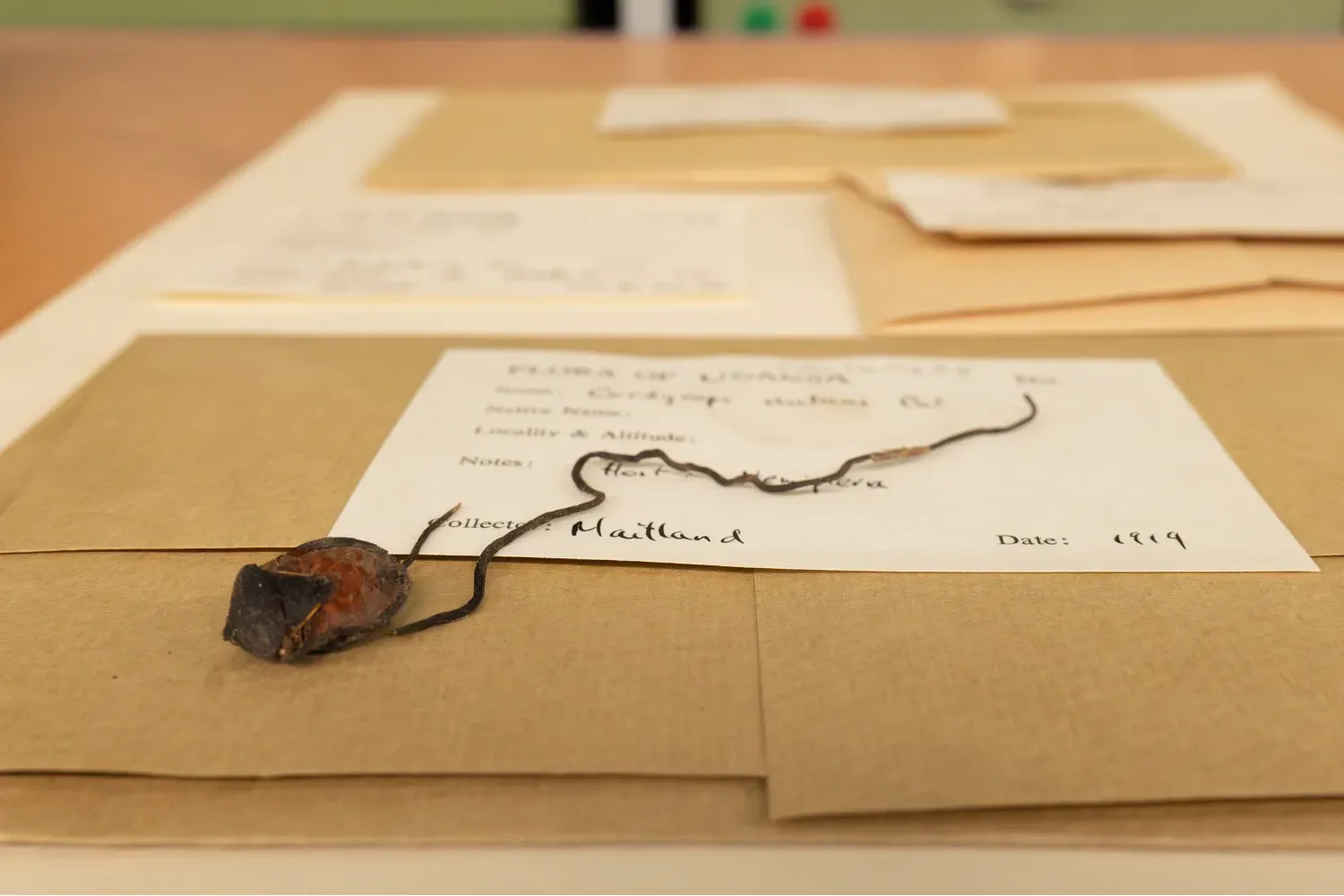

6. (Another) Insect-infecting fungi (Cordyceps) - Ophiocordyceps nutans

We’re fascinated by these fungi – so wanted to include another here. Namely, Ophiocordyceps nutans: a parasitic fungus that was found growing from a Hemipteran shieldbug, demonstrating the remarkable lifecycle of Cordyceps fungi.

Once infected, the insect host is effectively hijacked, its body used as a platform for the fungus to reproduce. The fungal specimen reveals the dramatic moment the fruiting body erupts from the insect - an incredible example of nature’s more macabre strategies. These fungi are of growing interest to researchers studying parasitism, biocontrol, and even pharmacology.

Because of its appetite for certain insects, O. nutans has been proposed as a natural insecticide against stinkbugs, which are known to cause significant damage to certain agricultural crops.

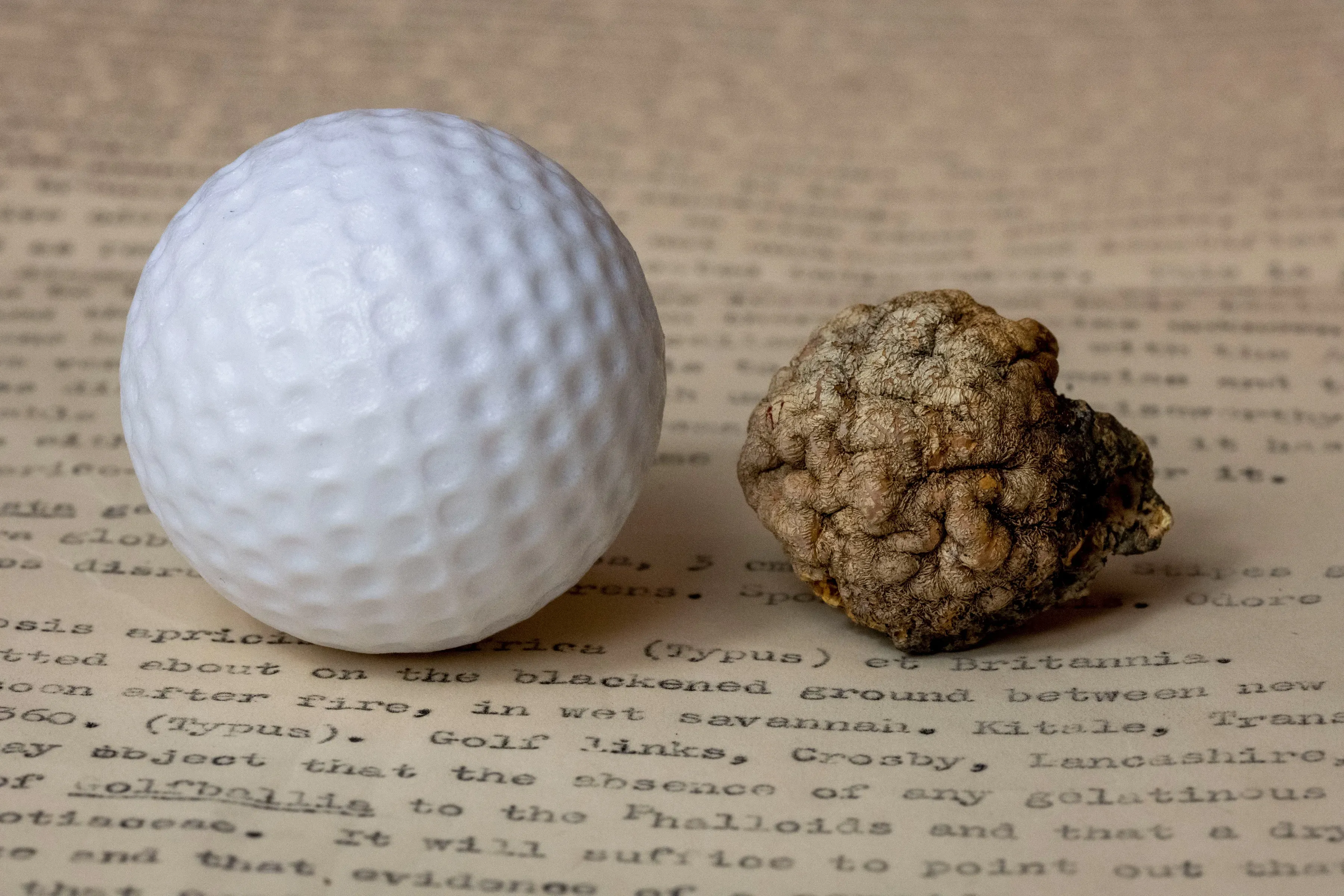

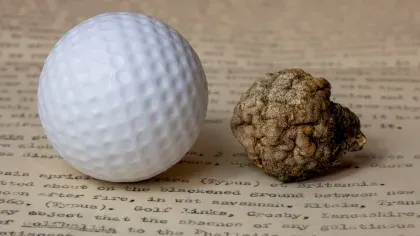

7. The legendary Golfballia ambusta

Little is known about this species' exact origins other than that the first specimen arrived at Kew in 1952 from Lancashire. At first glance it strongly resembled some sort of puff ball-like fungus but upon further examination it was revealed to be a... burnt golf ball.

And yet, when another specimen arrived through Kew's letterbox some years later, the Head of Mycology at the time, Dr R.W.G Dennis, decided to pull a prank on the wider scientific community. Although his exact reasoning is unknown he officially described the damaged sporting equipment as a new species in Journal of the Kew Guild.

And so, in 1962, in a paper titled ‘A Remarkable New Genus of Phalloids in Lancashire and East Africa’, the 'fungal' species Golfballia ambusta was revealed to the world. Described as ‘small, hard but elastic, spheres enjoyed by the Caledonians in certain tribal rites’, its scientific name quite literally translates to burnt golf ball.

Unlocking a Hidden Kingdom

These are just a few of the extraordinary specimens we’ve uncovered as we work to bring the world’s largest collection of dried fungi into the digital age. From insect-infecting parasites to fungi discovered by Darwin, every specimen tells a story - of biodiversity, of exploration, and of the critical role fungi play in life on Earth.

Since 2024, Kew’s scientists have also been tapping into the genetic information stored within the Fungarium’s 45,000 type specimens or holotypes – these are the definitive reference specimens attached to scientific names. The Fungarium Sequencing Project looks to sequence more than 10,000 of these fungi, making the data open source and publicly available online over the coming years, unlocking in the process new compounds and genetic secrets that could accelerate the discovery of new useful chemicals and medicines.

With over 1.1 million specimens now imaged, the next step is transcription and quality assurance, after which the entire collection will be freely accessible through our Data Portal. Whether you’re researching global plant health, studying climate change, or simply curious about the fungi beneath your feet, this collection will be yours to explore.

As Shaheenara Chowdhury, our Digitisation Fungarium Operations Manager, reflects:

“Fungi are some of the planet’s most powerful, mysterious, and overlooked organisms. By bringing our collection online, we’re not just preserving the past, we’re opening the door to discoveries that haven’t yet been imagined. It's wonderful to know that these specimens can now be explored anywhere in the world by researchers, students, and inquisitive minds.”

We couldn’t agree more.

Acknowledgments

The digitisation of our collections and the online portal have been part-funded by Defra, appeal supporters, private philanthropists, Fujifilm Electronic Imaging Europe GmbH, The HDH Wills 1965 Charitable Trust, and the first Chairman of Kew’s Board of Trustees, Lord John Eccles.

.png2082.webp?itok=lYHL_dmh)