30 April 2025

5 min read

Guardians of the soil: racing for restoration in the British Virgin Islands

The secrets of the soil hold to the key to ecosystem restoration in the Caribbean. Can we unlock them from the Kew Quarantine House?

On two remote islands in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), conservationists, scientists, and local partners are working together to unearth a story that begins in the soil. It is a story of resilience, recovery, and rapid response to protect some of the Caribbean’s most special native habitats.

Great and Little Tobago are internationally recognised Key Biodiversity Areas and Important Plant Areas in the UK Overseas Territories. These islands are home to nesting colonies of magnificent frigatebirds, brown boobies and pelicans as well as the threatened plant Agave missionum - but the island’s biodiversity has long been under threat from invasive species.

Feral goats have had devastating impacts on the native vegetation on these islands by grazing and trampling. The resulting soil compaction and erosion has exacerbated topsoil loss. All of this damages the ability of seeds to germinate and seedlings to establish, harming plant populations.

Thanks to a suite of projects supported by the Darwin Plus funding scheme, biodiversity on these islands is being offered a lifeline. DPLUS215, a project led by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the National Parks Trust of the Virgin Islands (NPTVI), is working to understand and restore the natural plant communities of the islands, from the ground up.

Restoring Balance

While feral goats once roamed freely across Great and Little Tobago, their removal is underway thanks to the DPLUS196 project, led by the RSPB in collaboration with Kew, NPTVI and others. But with one threat diminished, another looms: the risk of non-native plants surging in to take their place.

The question is what lies in the soil? Seeds, both native and invasive, can lie dormant for years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate. Understanding what species are hidden in the soil seedbank is key to guiding restoration efforts and preventing invasive plants from establishing a new foothold.

That’s where our initiative comes in. The project is establishing a baseline of plant species present in the soil, to understand exactly what’s there, and guide future habitat restoration and species reintroduction.

What Lies Beneath

In 2024, the NPTVI team collected 100 soil samples from the Tobago Islands: 70 from Great Tobago in June and 30 from Little Tobago in November. Each sample was carefully air-dried to prevent seeds from prematurely germinating, and then triple-bagged to ensure safe transport, in line with the UK’s own vital biosecurity regulations.

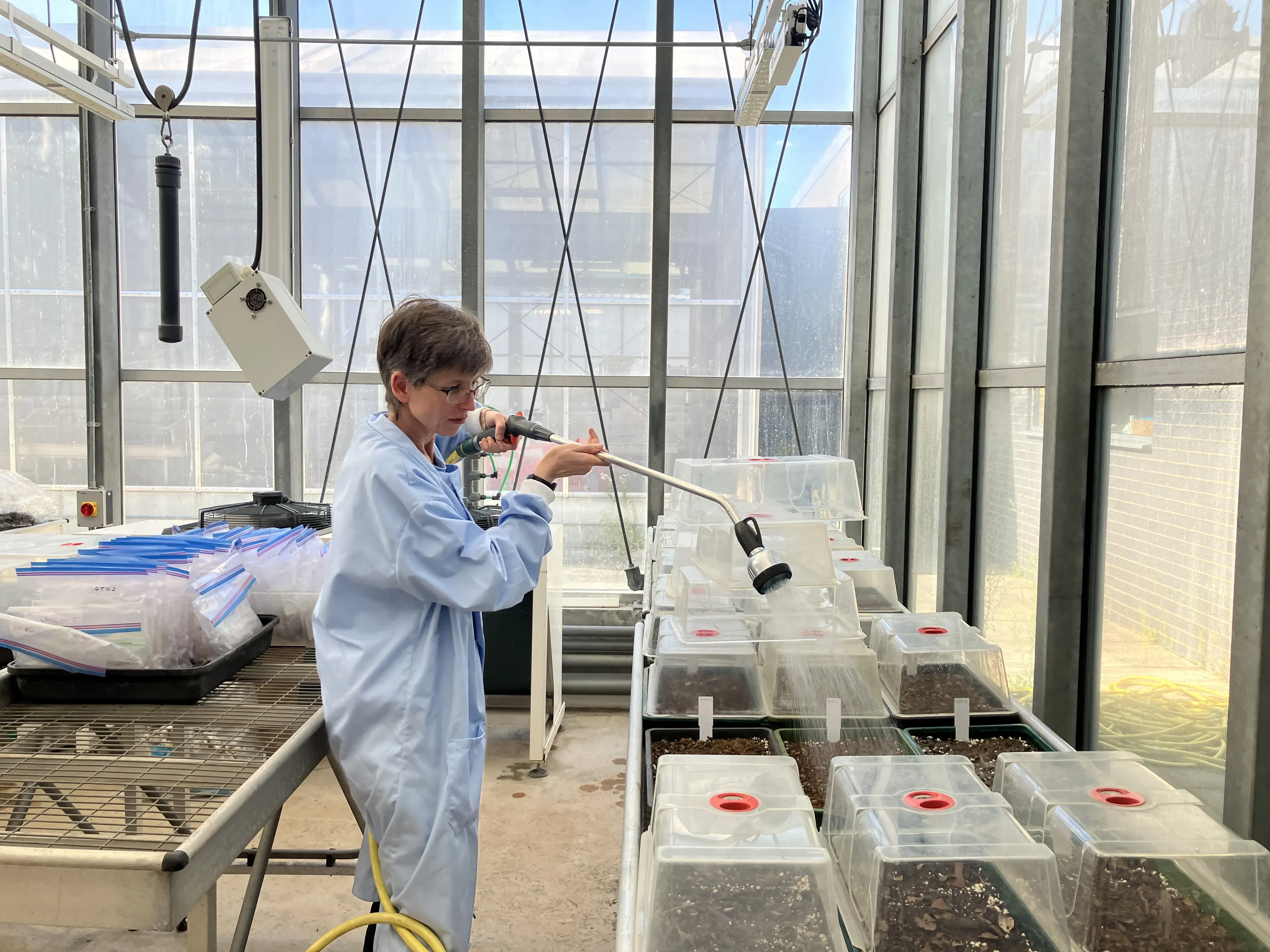

The bags were shipped to Kew’s Quarantine House, where the next chapter of this restoration story began.

At Kew, the soil was spread in thin layers on sterilised compost trays and placed in climate-controlled bays that simulate dry forest conditions. Within five days, tiny green shoots began to emerge.

“Watching the first seedlings appear felt like a breakthrough. If each of these seedlings were of native species, it would mean that there’s hope in the soil.”

Dr Rosemary Newton

The process of identifying seedlings is no small feat. Many look nearly identical in early growth stages. To overcome this, every single seedling is being harvested and sent for DNA sequencing. So far, over 3,000 seedlings have been collected and processed.

A Genomic Map of the British Virgin Islands

To make sense of what’s germinating, the seedlings are being matched against DNA libraries of native and non-native plant species. This comparative work is supported by another Darwin-funded project, DPLUS183, which is cataloguing all known native flowering plants (angiosperms) of the BVI. Our soil project is complementing this by building a similar library of the non-native species likely to be present in the soil.

Together, these datasets are creating a “genomic library”, essentially a digital fingerprint bank, of the flora of the Virgin Islands.

“By comparing the seedling DNA against both reference sets, we can quickly determine what’s native and what isn’t. It’s a powerful approach that brings together botany, molecular science and conservation action.”

Dr Rosemary Newton

This kind of work allows the team to not only see what’s emerging now, but also to forecast what might need intervention in the future. If key native species are missing, they can be introduced. If invasive species begin to reappear, targeted control can begin early.

Science Meets Strategy

Crucially, this data doesn’t just sit in lab notebooks. It’s actively informing on-the-ground decisions by the NPTVI and its partners. The seedbank results help identify which areas are recovering well and which might need additional support. It also allows restoration plans to be tailored to the specific species present in each area, making conservation efforts more targeted, more efficient, and more sustainable in the long term.

Rather than relying solely on replanting, the project takes a more holistic approach: using what the land already holds to guide its own recovery. It’s a method that’s grounded in science but rooted in local context and respect for the natural resilience of these ecosystems.

Looking Forward

The restoration work is still in its early stages, but the signs are promising, with some native species already identified. The genomic library is growing by the week, and new findings are already being shared with collaborators in the BVI.

As the project progresses, community engagement will also play a key role, sharing native biodiversity knowledge with those that call the British Virgin Islands their home, and increasing their connection with it.

“Every seedling that grows brings us closer to restoring balance. It’s not just about plants, as they provide critical habitat for endangered nesting seabirds. Restoring the vegetation helps the ecosystem to recover, safeguarding the future of these islands.”

Dr Rosemary Newton

Through DPLUS215 and its companion projects, the British Virgin Islands are showing what’s possible when science, local stewardship and long-term vision come together. And with each tiny leaf that unfurls, a fragile ecosystem takes one step closer to renewal.

The DPLUS215 project is funded by the UK Government through Darwin Plus

.jpg5685.webp?itok=AReKAqLL)

Plant diversity in the British Virgin Islands, linking the past with the present

Rattan palms and the origins of tropical Asian rainforest diversity