15 July 2025

5 min read

What is a seed?

It might seem like a simple question, but how much do you know about these precious packages of potential plant life?

Seeds are crucially important to all life on the planet.

These potent bundles of growth develop into plants that provide us with food, shelter and the ecosystems that produce the very air we breathe.

Almost 350,000 species of plants produce them. But what actually IS a seed? Where did they come from? What’s their role? And why are they more important than ever in combatting biodiversity loss and climate change?

The structure of a seed

There are around 350,000 plants that produce seeds or, to give them their scientific name, spermatophytes.

Seed producing plants come in two varieties: angiosperms and gymnosperms.

Angiosperms, meaning “contained seeds” are better known as flowering plants. This group makes up over 90% of seed producing plants, with over 300,000 named species.

With so many different species, there’s a tremendous amount of variety in seed types. But most angiosperm seeds have three key features: an embryo, a food supply and a seed coat.

The embryo is essentially a very small version of the young plant. It has basic structures that will develop into sprouting leaves and roots.

The food supply is the lunch box for the young plant. It’s made up of proteins, oils and starch and provides a source of food to the young growing plant. You’ll probably best know this food supply as the part of bread wheat that we turn into flour.

Finally, there’s the seed coat. This outer layer keeps the seed protected until the conditions are just right for the seed to germinate. The seed coat stops the seed from drying out and protects the embryo from potential damage.

All angiosperm seeds are contained within a fruit, which can range from something as big as a pumpkin to as small as the husk of a sunflower seed.

What’s a gymnosperm?

However, there’s another type of seed that can’t be overlooked: gymnosperm seeds.

The translated name of gymnosperms, “naked seeds”, is a clue to what makes them different to angiosperms.

Gymnosperm plants include conifers, like stone pines or giant redwoods, and the desert dwelling Welwitschia mirabilis.

The majority of gymnosperms don’t produce fruit to encapsulate seeds. Instead, many of them produce cones that are made up of several small woody scales that protect the young seeds in between them.

Some gymnosperms produce structures which on first glance look like fruits. But looks can be deceiving.

For instance, the red berries of a yew tree are in fact arils, heavily modified fleshy leaves that grow up around the seed to attract birds.

Similarly, juniper berries aren’t true fruits at all, but in fact the fleshy female seed cone of the tree. Odd to think that gin is flavoured by a tree cone!

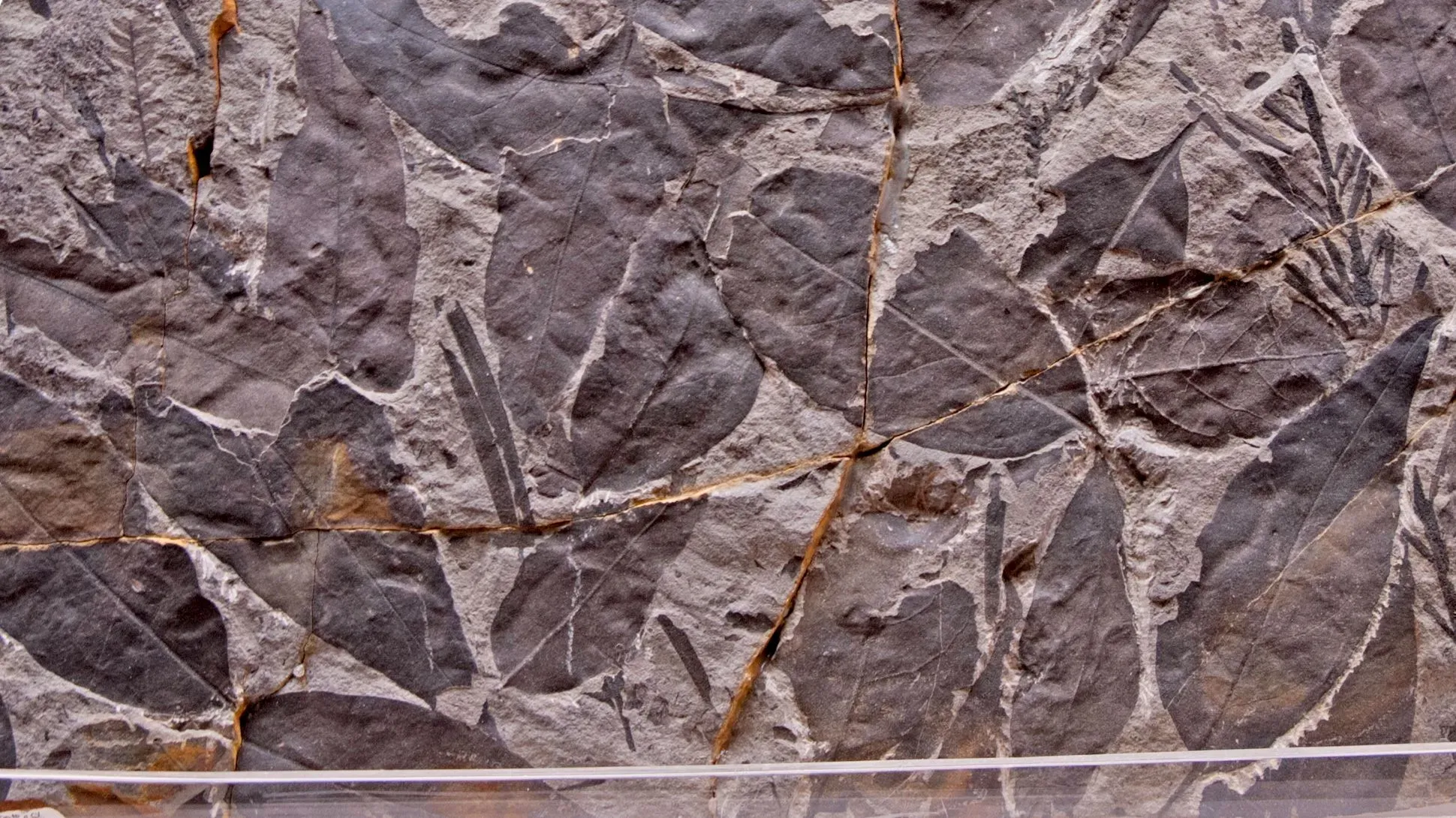

The history of seeds

Land plants are thought to have first appeared around 470 million years ago, but they didn’t reproduce using seeds. Instead, they used spores, like modern day ferns and clubmosses.

It wasn’t for another 100 million years until we saw the earliest seed-bearing gymnosperms appear, somewhere around 340 million years ago in the Early Carboniferous period.

Then, 130 million years ago, in the middle of the age of the dinosaurs, flowering plants appeared across the world. While it’s still unclear exactly where and how the flowering plants evolved, they rapidly became one of the most dominant forms of plant life across the planet.

Today, flowering plants are found on every continent on the planet, including two species native to Antarctica.

Why are seeds important?

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of plants to our world.

Around 90% of humanity’s calories come from crop plants, including rice, wheat and maize. Trees provide us with the materials used to create books, furniture and many of the buildings we call home. And that doesn’t even touch on the critical part that plants play in our ecosystems, providing homes to literally millions of animal species and providing us with clean air to breathe.

So the fact that around 45% of flowering plant species are thought to be at risk of extinction is a stark piece of news.

As habitats continue to be destroyed by human activity and climate change, we need to be able to restore lost plant life with an insurance plan.

That’s where the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) at Wakehurst comes in.

The Seed Collection at the MSB contains nearly 2.5 billion seeds, representing almost 40,000 different plant species.

The MSB, and other seed banks like it, are the perfect way for long-term, ex-situ (away from their natural habitat) plant conservation.

At Kew, seeds are collected through global partnerships as part of the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership (MSBP) network. Once stored in the MSB, they become a freely available resource for both research and projects looking to restore damaged or destroyed ecosystems all over the world.

Seeds provide the perfect way to protect species into the future. Millions of years of evolution have perfected seeds for the primary role of dispersal and survival of plant species.

Some species, like the date palm or the sacred lotus have seeds that can remain dormant for centuries if not millennia.

But seeds are rarely naturally this long lived. Despite all their natural protection, they can still fall prey to rot or disease. And over a long enough time, all cells will degrade through processes like oxidisation. To prevent this, seeds in our collections are first dried out, then stored at -20°C. All our seed collections are checked at regular intervals to see if they can still sprout into healthy plants.

Seeds are little packages of life, just waiting for the right moment to burst into being. They’ve helped make plants one of the most widespread forms of life on our planet. And now, they might be the single best chance to stop biodiversity loss in the face of climate change and human impact.